Learning Forum: All You Need to Know About Factor Analysis

Factor analysis is a statistical technique that helps us understand the underlying structure of a set of observed variables. It delves into the world of hidden influences, represented by latent variables, that explain the relationships between the things we can directly measure (observed variables).

Here’s a breakdown of the key concepts:

- Observed Variables.

- Latent Variables (Factors).

- Common Variance: This is the variation in the observed variables that can be explained by the factors.

- Unique Variance: This is the variation in each observed variable that’s not explained by the factors and might be due to random errors or specific characteristics.

Observed Variables

Imagine you’re studying personality. You might use a questionnaire with questions like “I enjoy being the center of attention” or “I am organized and neat.” These are your observed variables. They are the concrete measurements you collect through surveys, experiments, or other data gathering methods.

Latent Variables

But what if these seemingly unrelated questions tap into a deeper concept, like extroversion or conscientiousness? These underlying, unobservable traits are the latent variables. You can’t directly measure extroversion, but you can see its influence on how someone answers questions about socializing or tidiness.

The Process of Factor Analysis:

- Data Collection: You start with a dataset containing multiple variables you suspect are influenced by some hidden factors.

- Factor Extraction: Statistical methods identify a smaller number of factors that explain most of the variation in the observed variables. There are different techniques for extraction, like Principal Component Analysis.

- Factor Rotation: This step aims to improve the interpretability of the factors. Imagine rotating the fruit basket to get a clearer view of how the fruits group based on factors.

- Interpretation: You analyze the factors and observed variables to understand the underlying meaning of the factors. In the fruit example, you might name a factor “Citrus” based on its strong correlation with sweetness and acidity.

Benefits of Factor Analysis:

- Data Reduction: It simplifies complex datasets by identifying a smaller number of key factors.

- Identify Underlying Patterns: It reveals hidden relationships between variables that might not be obvious at first glance.

- Model Building: Factors can be used to create new variables or scoring systems for further analysis.

Applications of Factor Analysis:

- Psychology: It’s used to understand personality traits, intelligence, and mental health.

- Marketing: It helps identify customer segments based on buying habits and preferences.

- Finance: It can be used to assess financial risk or group stocks based on common factors.

- Social Sciences: It can analyze survey data to uncover underlying social and economic trends.

Things to Consider:

- Factor analysis assumes certain conditions about the data, so it’s important to check those assumptions before applying it.

- Interpreting factors can be subjective, so careful analysis and domain knowledge are crucial.

Confirmatory vs Exploratory Factor Analysis

| Feature | Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) | Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Tests a pre-defined factor structure | Discovers the underlying factor structure |

| Starting Point | Existing theory or hypothesis about factors | Large dataset with interrelated variables |

| Number of Factors | Predetermined number of factors | Data-driven; number of factors is explored |

| Factor Loadings | Estimates how well each variable reflects the proposed factors | Identifies which variables group together under potential factors |

| Interpretation | Focuses on confirming the hypothesized relationships | Focuses on exploring and interpreting newly discovered factors |

| Flexibility | Less flexible; requires a strong theoretical foundation | More flexible; allows for unexpected factor structures to emerge |

| Use Case | Validating existing scales or measurement models | Developing new scales, understanding complex datasets |

Additional Points:

- CFA is typically used after EFA to confirm the structure identified through exploration.

- EFA is generally considered the first step in factor analysis, while CFA is used for further validation.

- Both methods rely on statistical tests to assess the model fit and factor loadings.

Example: Exploring Personality Traits with EFA

Imagine you’re a psychologist studying personality. You collect data from a group of students using a survey with various questions related to personality traits. Here’s how EFA could be applied:

Data:

- You have survey responses from 200 students on 20 different questions.

- These questions cover aspects like:

- Extraversion (e.g., enjoys social gatherings, prefers talking)

- Neuroticism (e.g., anxious, worries easily)

- Agreeableness (e.g., helpful, trusts others)

- Conscientiousness (e.g., organized, detail-oriented)

- Openness to Experience (e.g., enjoys novelty, intellectual curiosity)

EFA Steps:

- Data Preparation: Ensure your data meets the assumptions of EFA (e.g., normality, linearity).

- Factor Extraction: You use an EFA technique like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify a smaller number of factors that explain the most variance in the 20 questions.

- Determining the Number of Factors: You might use techniques like the Scree plot (a graph) to decide how many factors to retain. The Scree plot will show a clear “elbow” where the explained variance by additional factors drops off significantly.

- Factor Rotation: You might rotate the factors (like rotating the fruit basket) to improve their interpretability. This doesn’t change the underlying structure but makes it easier to understand which questions relate to each factor.

- Interpretation: You analyze the questions with high loadings on each factor. Here’s a possible outcome:

- Factor 1: High loadings on questions related to social interaction, talkativeness, and enjoying company (Extraversion).

- Factor 2: High loadings on questions about anxiety, worry, and emotional reactivity (Neuroticism).

- Factor 3: High loadings on questions about helpfulness, trust, and cooperation (Agreeableness).

Benefits:

- By identifying these factors, you can create a more concise personality assessment tool based on a smaller number of questions.

- Understanding the underlying factors can shed light on how personality traits manifest in behavior.

Limitations:

- EFA doesn’t tell you the exact names of the factors – that requires interpretation based on your knowledge of personality psychology.

- The results might be influenced by the specific questions chosen in the survey.

This is a simplified example, but it demonstrates how EFA can be used to explore and understand the underlying structure of complex data related to human behavior.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) focuses on discovering the underlying structure of your data, so there aren’t definitive goodness-of-fit indices like in Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). However, there are several approaches to assess how well the extracted factors represent the data in EFA:

1. Kaiser’s Eigenvalue Criterion:

This common rule suggests retaining factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. An eigenvalue represents the amount of variance explained by a factor. Values greater than 1 indicate the factor explains more variance than a single observed variable.

2. Scree Plot:

This visual tool plots the eigenvalues of each factor. Look for an “elbow” where the explained variance by additional factors drops off significantly. Factors before the elbow are typically retained.

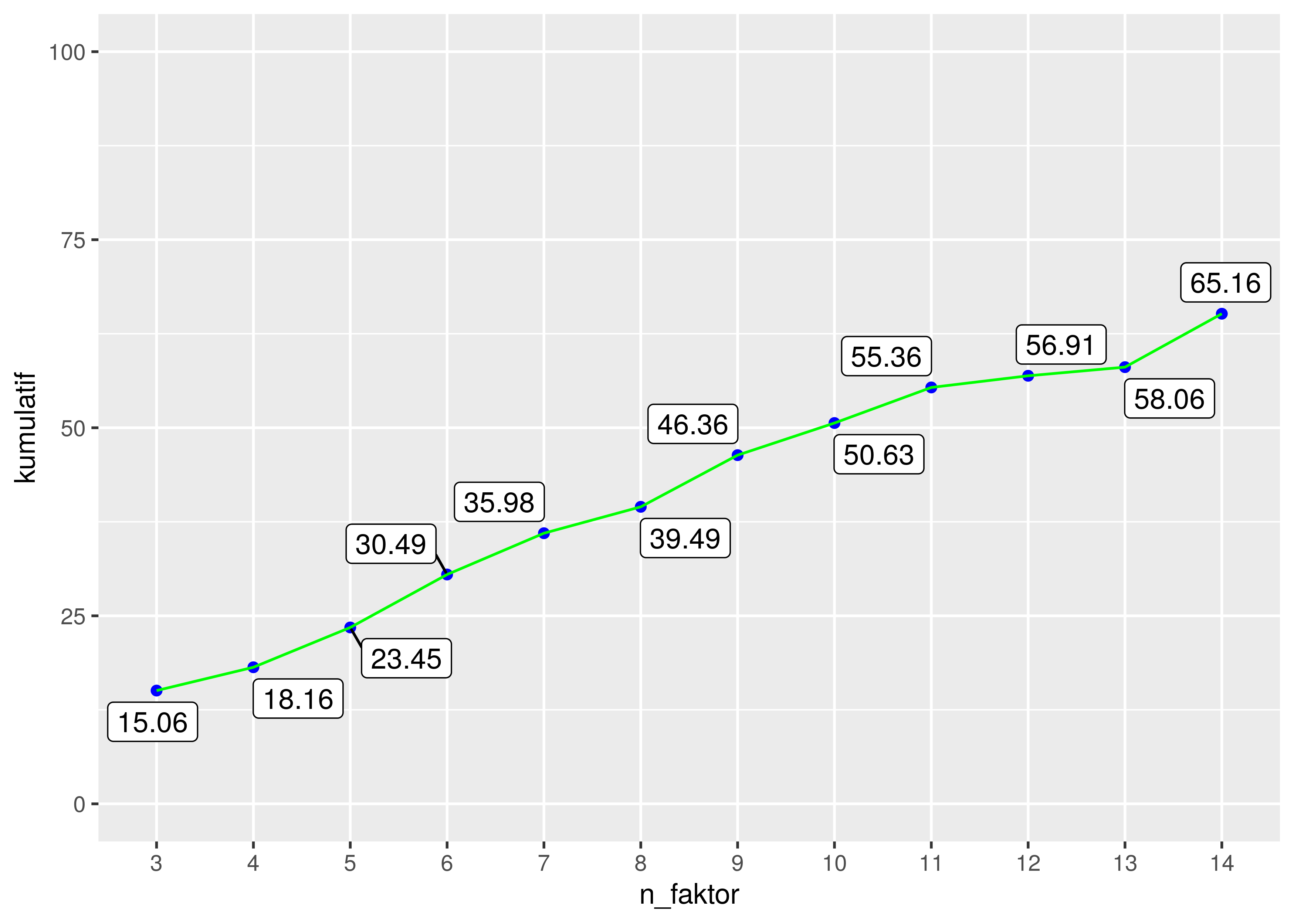

3. Percentage of Variance Explained:

Calculate the percentage of variance explained by the retained factors. Higher values suggest the factors capture a substantial portion of the data’s variability.

4. Factor Loadings:

These coefficients indicate how strongly each observed variable relates to a specific factor. Aim for high loadings (> .4) on a single factor for each variable, and low loadings on other factors. This suggests clear associations between variables and their corresponding factors.

5. Interpretability of Factors:

Can you make sense of the factors based on the variables with high loadings? Do the factors align with your understanding of the data and research questions?

While these methods are helpful, they shouldn’t be used in isolation:

- The ideal number of factors can be subjective, and different criteria might suggest slightly different solutions.

- Consider the research context and the interpretability of the factors when making decisions.

Here are some additional points to remember:

- Sample Size: Larger samples tend to lead to more extracted factors, so consider your sample size when interpreting results.

- Data Quality: Ensure your data meets the assumptions of EFA (e.g., normality, linearity) for more reliable results.

By combining these methods and considering your research goals, you can gain valuable insights from EFA and identify the most relevant factors for further analysis.

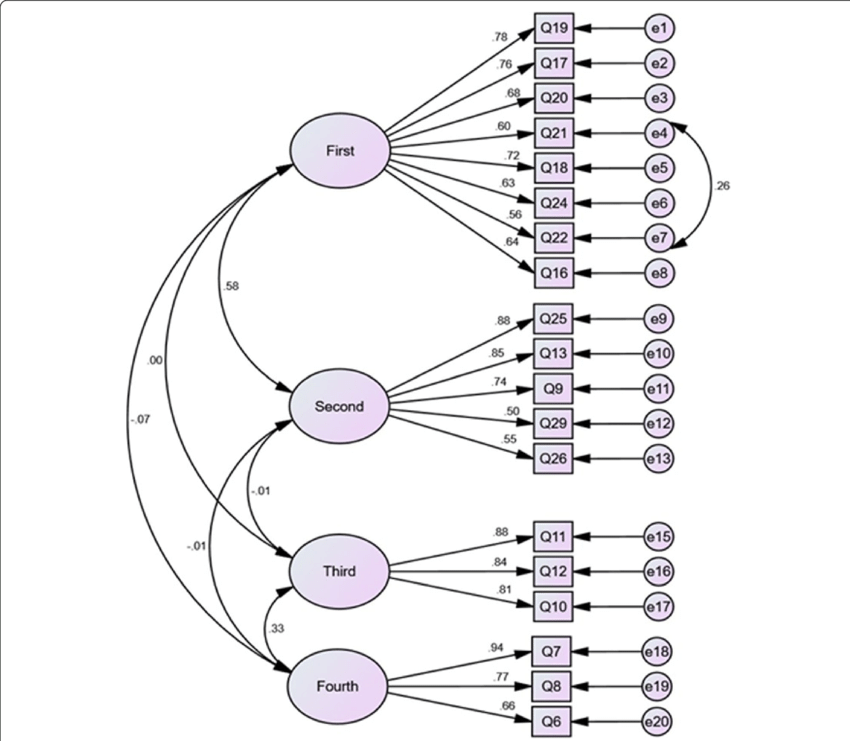

Example: Validating a Customer Satisfaction Scale with CFA

Imagine you work for a company developing a new customer satisfaction survey. You’ve designed a scale with five questions to measure overall customer satisfaction:

- Question 1: How satisfied are you with the product quality? (1 = Very Dissatisfied, 5 = Very Satisfied)

- Question 2: How easy was it to use the product? (1 = Very Difficult, 5 = Very Easy)

- Question 3: How helpful was customer support? (1 = Not Helpful at All, 5 = Extremely Helpful)

- Question 4: How likely are you to recommend this product to others? (1 = Not Likely at All, 5 = Extremely Likely)

- Question 5: Overall, how satisfied are you with your experience with our company? (1 = Very Dissatisfied, 5 = Very Satisfied)

You believe these questions all tap into a single underlying factor – “Customer Satisfaction.” Here’s how CFA could be applied:

Steps:

-

Hypothesized Model: You specify a model in software like Mplus or lavaan that depicts the relationship between the five questions (observed variables) and the single latent factor (customer satisfaction).

-

Data Analysis: You run the CFA analysis using data collected from a sample of your customers who completed the survey.

-

Evaluation of Fit: The software provides various fit indices (e.g., Chi-square, CFI, RMSEA) to assess how well your hypothesized model (one factor) explains the data.

-

Interpretation:

- Good Fit: If the fit indices suggest a good fit, it provides evidence that the five questions indeed measure a single underlying construct – customer satisfaction. The factor loadings (strength of the relationship between each question and the factor) can be examined to see how strongly each question contributes to the overall satisfaction score.

- Poor Fit: If the fit is poor, it suggests the data doesn’t support your one-factor model. You might need to re-evaluate the survey or explore alternative models with multiple factors.

Benefits:

- CFA provides statistical evidence to support the validity of your customer satisfaction scale.

- Understanding factor loadings helps you refine the survey by identifying the most relevant questions.

Limitations:

- CFA relies on strong theoretical justification for the hypothesized model.

- Poor fit indices might not always be due to a faulty model; data quality issues could also contribute.

This example showcases how CFA can be used to confirm the structure of a measurement tool and ensure it accurately reflects the underlying concept you’re trying to assess.

Goodness-of-Fit Indices in Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Here’s a table summarizing common goodness-of-fit indices used in CFA:

| Index | Description | Recommended Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square (χ²) | Absolute measure of model fit based on the difference between observed and model-predicted covariance matrices. | Not a definitive measure on its own; sensitive to sample size. A lower χ² is better. | Use in conjunction with other indices; non-significant χ² suggests good fit, but significance doesn’t necessarily mean bad fit. |

| Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) | Proportion of variance explained by the model. | > .90 | Higher values indicate better fit. |

| Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI) | Adjusts GFI for model complexity (number of parameters). | > .85 | Higher values indicate better fit, especially for complex models. |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | Compares the fit of the hypothesized model to a null model with no relationships. | > .90 | Higher values indicate better fit. |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | Compares the fit of the hypothesized model to a baseline model with no latent variables. | > .95 | Higher values indicate better fit. |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | Estimate of average error of approximation per degree of freedom. | < .08 (good), .08-.10 (acceptable) | Lower values indicate better fit. |

Important Notes:

- There are no strict cutoffs for all indices, and researchers often consider a combination of multiple indices to evaluate model fit.

- The recommended values might vary slightly depending on the specific software and reference source.

- Other fit indices also exist, but these are some of the most commonly used.

By examining these indices, you can assess how well your hypothesized factor structure aligns with the actual data in your CFA analysis.

The R Codes

R code for Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using base

Survey data:

V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 V6 V7 V8 V9 V10 V11 V12 V13 V14 V15 V16 V17 V18 V19 V20

1 2 3 4 4 2 4 0 3 3 4 4 1 4 3 4 5 3 3 4 3

2 3 3 3 2 4 3 4 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 4 4 5 3 2

3 3 4 3 2 4 4 4 2 3 3 5 2 3 3 3 4 3 5 4 3

4 3 3 4 4 4 4 1 4 5 2 3 3 4 5 3 2 4 2 2 2

5 3 3 2 5 3 5 4 2 3 4 3 4 1 4 5 3 3 2 4 3

6 5 4 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 4 5 4 6 3 2 2 1 2 2 4

Let’s perform factor analysis using 14 factors:

Call:

factanal(x = df, factors = 14, scores = "regression", rotation = "varimax")

Uniquenesses:

V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 V6 V7 V8 V9 V10 V11 V12 V13

0.397 0.490 0.695 0.005 0.722 0.005 0.861 0.827 0.233 0.005 0.564 0.005 0.005

V14 V15 V16 V17 V18 V19 V20

0.005 0.690 0.008 0.005 0.678 0.005 0.763

Loadings:

Factor1 Factor2 Factor3 Factor4 Factor5 Factor6 Factor7 Factor8 Factor9

V1 -0.114 -0.109 0.134

V2 -0.244 0.162 -0.149 0.123 -0.151

V3 -0.101 -0.128

V4 -0.102 0.959

V5 -0.176 0.113 -0.145 -0.144

V6 -0.130 0.964

V7 0.141 -0.229 -0.146

V8

V9 -0.175

V10 0.979

V11 -0.185 -0.158 0.152 -0.156

V12 0.968

V13 0.978

V14 0.982

V15

V16 0.969

V17 0.981

V18 0.174 -0.235 0.211 0.224

V19 0.972

V20 0.153 -0.167 0.118

Factor10 Factor11 Factor12 Factor13 Factor14

V1 -0.733

V2 -0.191 0.406 -0.164 0.356

V3 0.184 0.479

V4 0.106 0.106 0.163

V5 0.120 -0.381

V6 0.171

V7 0.105

V8 -0.402

V9 0.847

V10 -0.102

V11 0.120 0.384 -0.233 0.271 0.168

V12 -0.172 -0.106

V13 0.137

V14 0.107

V15 0.521

V16 -0.191

V17

V18 -0.138 0.155 0.188 0.115 0.214

V19 0.144

V20 0.238 -0.307

Factor1 Factor2 Factor3 Factor4 Factor5 Factor6 Factor7 Factor8

SS loadings 1.145 1.086 1.085 1.084 1.080 1.043 1.036 1.027

Proportion Var 0.057 0.054 0.054 0.054 0.054 0.052 0.052 0.051

Cumulative Var 0.057 0.112 0.166 0.220 0.274 0.326 0.378 0.429

Factor9 Factor10 Factor11 Factor12 Factor13 Factor14

SS loadings 1.003 0.861 0.790 0.720 0.659 0.412

Proportion Var 0.050 0.043 0.040 0.036 0.033 0.021

Cumulative Var 0.479 0.522 0.562 0.598 0.631 0.652

Test of the hypothesis that 14 factors are sufficient.

The chi square statistic is 0.38 on 1 degree of freedom.

The p-value is 0.538

R code for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) using the lavaan package

Here’s an example using lavaan for a simple CFA model:

q1 q2 q3

1 3.106891 5.847764 1.664618

2 1.830471 3.684917 2.466294

3 4.824100 5.956495 1.731595

4 1.544883 6.234212 2.687413

5 3.640874 1.183849 2.398501

6 4.811835 6.089416 1.347337

The hypothesized model is: f1 =~ q1 + q2 + q3.

Herewith the CFA:

lavaan 0.6-18 ended normally after 44 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 6

Number of observations 100

Model Test User Model:

Test statistic 0.000

Degrees of freedom 0

Model Test Baseline Model:

Test statistic 1.733

Degrees of freedom 3

P-value 0.630

User Model versus Baseline Model:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 1.000

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 1.000

Loglikelihood and Information Criteria:

Loglikelihood user model (H0) -431.257

Loglikelihood unrestricted model (H1) -431.257

Akaike (AIC) 874.513

Bayesian (BIC) 890.144

Sample-size adjusted Bayesian (SABIC) 871.195

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation:

RMSEA 0.000

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.000

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.000

P-value H_0: RMSEA <= 0.050 NA

P-value H_0: RMSEA >= 0.080 NA

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual:

SRMR 0.000

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Standard

Information Expected

Information saturated (h1) model Structured

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|)

f1 =~

q1 1.000

q2 1.042 2.043 0.510 0.610

q3 0.730 2.461 0.296 0.767

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|)

.q1 1.216 0.324 3.749 0.000

.q2 4.344 0.683 6.359 0.000

.q3 0.276 0.152 1.819 0.069

f1 -0.077 0.268 -0.288 0.773